Table of Contents

- The Tolling Term Sheet in plain English (IM → Model Logic)

- Video Walkthrough (follow along in Excel)

- Translate the Term Sheet into Model Inputs

- 1) Revenue stream selection: keep the base case pure

- 2) Contract timing: COD start and full-term alignment

- 3) Price inputs: separate “real price” from escalation mechanics

- 4) Contracted proportion: preserve flexibility without breaking the base case

- 5) Compensation rule switches: availability vs curtailment (paid vs not paid)

- Build the CTA Revenue Engine in Excel (step-by-step)

- Sanity checks and common pitfalls (quick but critical)

- Why lenders like tolling (and what changes in other stacks)

- Wrap-up and next steps (Deal Lab + RVA Certification)

- FAQs

A BESS Tolling Agreement sounds almost too easy to model: take contracted capacity, multiply by a fixed $/kW-month price, apply escalation, and you’re done. In practice, that shortcut is exactly how many models end up overstating cashflows—because tolling revenue isn’t just a price and a capacity number. It’s a contracted capacity product with very specific performance rules, timeline mechanics, and lender expectations around what “applicable capacity” really means in each period.

The good news is that once you model the logic cleanly, tolling becomes one of the most transparent and bankable revenue stacks you can put into a project finance model. The key is to treat it the way a credit committee would: revenues settle on an AC basis at the point of interconnection, the contract defines what is paid and what is not paid, and any performance or deliverability shortfalls must show up as adjustments—not as hidden assumptions.

In this article, you’ll learn how to build a lender-clean capacity tolling revenue line in Excel, starting from a real deal-style term sheet and turning it into a structured set of inputs and formulas. We’ll cover the pieces that are often skipped—like timeline flagging, real-to-nominal price escalation, availability compensation rules, and the practical “guardrails” that prevent you from quietly paying yourself for capacity the project can’t deliver.

The Tolling Term Sheet in plain English (IM → Model Logic)

A BESS tolling agreement for a standalone battery is best understood as renting out the AC capacity of the asset. Instead of getting paid for energy sold (MWh), the project receives a contracted capacity payment—typically quoted in USD per kW-ac per month—while the offtaker controls dispatch. That’s why tolling is often viewed as the clean baseline structure in BESS project finance: revenue is predictable, contracted, and largely decoupled from merchant price volatility.

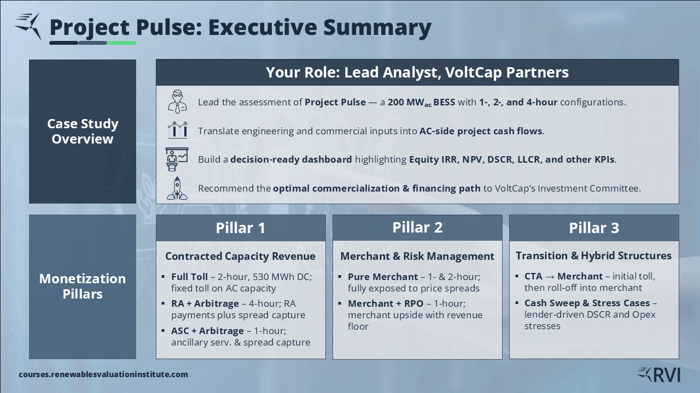

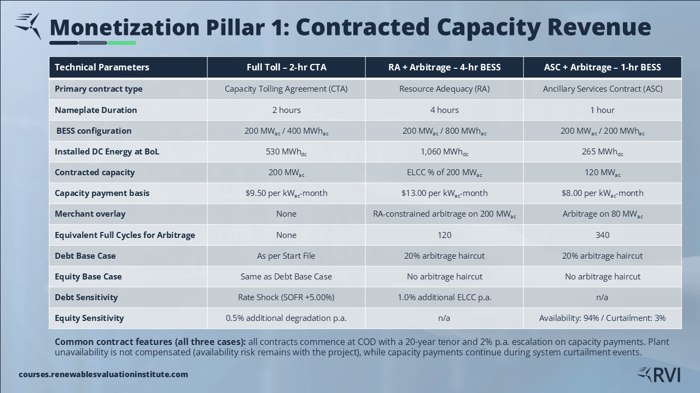

What the Project Pulse “Full Toll” case looks like

In the base case we’re modeling (case 1 in the Deal Lab), the battery is a 200 MW-ac system at the point of interconnection with a 2-hour product, which means 400 MWh-ac of nameplate energy. The tolling agreement covers 100% of the AC capacity for the full term. In other words, the offtaker is effectively reserving the battery’s grid-facing capability for the entire contract period.

Term, price, and escalation (the part everyone remembers)

The structure is straightforward:

Contract term: 20 years starting at COD (aligned with the asset life in the model)

Payment basis: fixed $9.5 per kW-ac-month (capacity payment)

Escalation: 2% per year, implemented as a time series escalation curve

This is the portion most models capture correctly: contracted capacity × contractual price × escalation.

The performance rules that matter (and drive the model structure)

Where tolling gets “real” is in the compensation rules—because they determine whether you get paid for 100% of contracted capacity in every period.

For the Project Pulse tolling case, the economic concept is:

Unavailability is not compensated. If the asset is down for technical reasons (maintenance, forced outage), the offtaker does not pay for that unavailable portion. Availability risk stays with the project.

Curtailment is compensated. If the system operator curtails the project for grid reasons, the tolling payment continues (i.e., the project isn’t penalized for being curtailed when it was otherwise available).

This single distinction is the reason a lender-clean model needs explicit switches for availability adjustment (typically on) and curtailment adjustment (often off under a compensated-curtailment CTA). It also explains why lenders may be more conservative than equity on availability assumptions unless there is a strong long-term service agreement with meaningful availability guarantees.

Why “capacity tolling” still needs deliverability discipline

Even though tolling is contracted, the product being sold is still a duration-defined AC deliverability product at the POI. Over long horizons, degradation and augmentation policy determine whether the asset remains capable of delivering that nameplate product. A robust model doesn’t wait for a breach to show up somewhere else—it builds a clear “applicable capacity” logic so revenue reflects the contract rules and the deliverability boundary of the product.

Video Walkthrough (follow along in Excel)

If you want to see the full build in real time before we break the model down into individual blocks, the video below walks through the exact BESS Tolling Agreement revenue implementation for the “Full Toll (CTA)” base case—starting from the information memorandum, validating the contract terms, and then building the revenue line step by step in the operations sheet.

You’ll see how the model stays lender-clean by:

turning the CTA on/off with a single flag (without touching the underlying formulas),

building the CTA price as real → nominal using an escalation time series,

converting contracted MW into the correct kW-ac unit required by $/kW-month products,

applying the right performance adjustments (availability is paid only when available; curtailment can be treated as compensated),

and adding a nameplate deliverability safeguard so capacity revenue can’t quietly assume 100% payment if deliverability would ever fall below the contracted product.

Deal Lab Part 4 — BESS Tolling Agreement Revenue Model in Excel

Translate the Term Sheet into Model Inputs

Before we write a single revenue formula, we want the BESS Tolling Agreement to live in the model as a clean set of inputs—so the operations sheet becomes a transparent calculation engine, not a place where commercial assumptions are buried. In Project Pulse, the key is to separate what the contract says (Inputs Time Independent) from how it evolves over time.

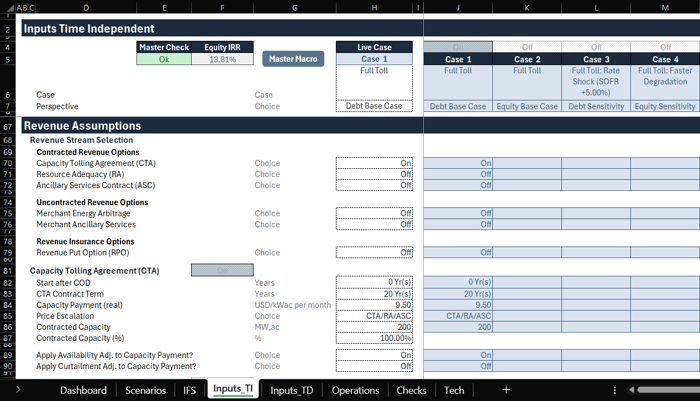

1) Revenue stream selection: keep the base case pure

Start by confirming that case 1 is truly the “clean baseline” structure:

CTA (capacity tolling agreement) = ON

all other revenue streams (RA, ancillary services, merchant arbitrage, put option, etc.) = OFF

This is important because it guarantees your cashflow stack reflects exactly what the term sheet describes: a single contracted capacity payment with no merchant overlay.

2) Contract timing: COD start and full-term alignment

In the CTA block, set up the timeline inputs so the agreement is active exactly when it should be:

Start after COD = 0 years (contract begins at COD)

Contract term = 20 years (aligned with the asset life in the base case)

These two inputs will later drive your CTA flag logic in the operations sheet. If the timeline inputs are right, the flag formula becomes a simple, reusable template you can apply across other contract types in later cases.

3) Price inputs: separate “real price” from escalation mechanics

For a BESS Tolling Agreement, the contractual payment is quoted as a real capacity price:

$9.50 per kW-ac-month (real price, before escalation)

Then, instead of hardcoding “2% escalation” inside the operations formula, you point the model to a time-series escalation curve in the Inputs Time Dependent sheet. This approach has two big advantages:

it keeps the logic modular (you can swap escalation assumptions without rewriting formulas),

and it scales cleanly when you later introduce alternative indexation approaches or sensitivities.

4) Contracted proportion: preserve flexibility without breaking the base case

Even though the base structure is 100% contracted, it’s best practice to include a “contracted proportion” input (e.g., 100% for case 1). That way, the model can later represent hybrid strategies—such as partially contracted capacity with a merchant overlay—without rebuilding the entire revenue engine.

This is one of those small design choices that makes your BESS Tolling Agreement block future-proof as you move through the other monetization pillars.

5) Compensation rule switches: availability vs curtailment (paid vs not paid)

This is where the contract becomes “real” from a modeling standpoint. The IM logic translates into two explicit switches:

Availability adjustment = ON (because unavailability is not compensated)

Curtailment adjustment = OFF by default (because curtailment is compensated in this structure)

By controlling these rules with switches, you avoid the most common modeling mistake: applying the wrong haircut to contracted capacity revenue. You can also easily stress-test alternative assumptions later (e.g., if a specific contract structure or lender overlay treats curtailment differently).

With these inputs validated, you’re ready to build the CTA revenue engine in Excel. Next, we’ll start with the CTA flag (timeline + on/off switch), then build the price (real → nominal), then build applicable capacity in kW-ac—before we combine everything into the final revenue line.

Build the CTA Revenue Engine in Excel (step-by-step)

Now we turn the inputs into a clean calculation engine. The goal is not just to “get a revenue number,” but to build a BESS Tolling Agreement block that is modular, auditable, and easy to stress-test—exactly what lenders and investment committees expect when they review a model.

At a high level, the workflow is:

create a CTA flag (timeline + on/off switch)

build the CTA price (real → nominal)

build applicable capacity (kW-ac) with the right adjustments

calculate CTA revenue with correct units and scaling

Below is the structure you’ll implement.

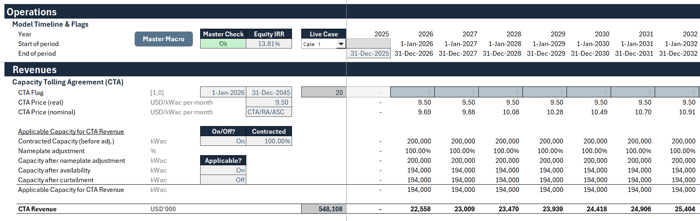

CTA Flag (timeline logic + revenue stream on/off)

The CTA flag is a simple 1/0 switch that answers: Is the contract active in this period for this case?

A lender-clean BESS Tolling Agreement model uses the flag to keep formulas stable—so if you turn CTA “off” in the inputs, revenue becomes zero everywhere without having to edit the underlying logic.

Mechanically, the flag checks:

the period start date is on/after the CTA start date, and

the period end date is on/before the CTA end date,

then multiplies by the CTA on/off input switch.

Result: you get a clean run of “1”s across the active contract term and “0”s elsewhere.

5.2 CTA price build (real price → nominal price)

Next, pull the real contractual CTA price (e.g., $9.5/kW-ac-month) and multiply it by the CTA flag so the price only appears during the contract term.

Then convert real to nominal using the escalation/indexation time series:

link your escalation selection (e.g., “2% escalation”)

use a lookup to pull the correct index curve from the time-dependent sheet

multiply the real price by that index to get nominal CTA price

This is important because it keeps your BESS Tolling Agreement price logic flexible. If you later change escalation, you update the time series—not dozens of formulas.

5.3 Applicable capacity build (kW-ac) with correct adjustments

CTA revenue is paid on capacity, not energy, so your capacity must be expressed in the correct unit for the contract price: kW-ac.

Start with:

gross POI capacity (kW-ac)

multiply by contracted proportion (% under the CTA)

multiply by the CTA flag

That gives you contracted kW before performance adjustments.

Now apply the three adjustment layers that keep the revenue line honest:

(a) Nameplate deliverability safeguard

Even though a CTA is contracted, it is still a duration-defined product. If degradation would cause a breach of deliverability, you should not assume 100% of nameplate is always payable. The safeguard applies a factor based on deliverable energy versus nameplate energy. In a properly structured model, augmentation prevents this from ever biting in the base case—but the safeguard matters because it:

catches unrealistic assumptions (e.g., “augmentation off” tests), and

prevents quietly overstated contracted cashflows.

(b) Availability adjustment (typically ON)

Because unavailability is not compensated under this CTA structure, you haircut the applicable capacity by availability when the “availability paid?” switch is on. If that switch is off, the model assumes 100% payment (useful for alternative contract structures or simplified cases).

(c) Curtailment adjustment (typically OFF here)

If curtailment is compensated (CTA payment continues), you generally do not haircut capacity for curtailment. But you keep the switch as optionality—because some contracts or lender overlays may treat this differently.

After these steps, you have a clean “Applicable Capacity for CTA Revenue” line that reflects the contract rules.

5.4 Final CTA revenue formula (units + scaling)

The final step is simply:

CTA Revenue = Applicable kW-ac × Nominal $/kW-ac-month × 12

Then apply:

÷ 1,000 if your model reports revenues in $000s (common in project finance models)

This unit discipline is worth calling out explicitly: many errors in tolling models come from mixing MW and kW, or forgetting the annualization factor implied by $/kW-month pricing.

In the next section, we’ll sanity-check the result (does the first-year revenue magnitude make sense?) and then highlight the most common mistakes analysts make when modeling a BESS Tolling Agreement—especially mistakes that can inflate DSCR/LLCR and mislead both debt and equity decisions.

Sanity checks and common pitfalls (quick but critical)

Once your BESS Tolling Agreement revenue line is built, don’t move on yet—do two fast sanity checks. They take minutes, but they’re exactly what prevents silent model errors from flowing into DSCR, LLCR, and IRR.

1) Sanity check the magnitude (back-of-the-envelope)

A tolling payment is a capacity rent, so the annual revenue should roughly look like:

200,000 kW × $9.5/kW-month × 12 ≈ $22.8 million per year (before escalation and haircuts)

If your first-year result is nowhere near that range, you likely have a unit issue (MW vs kW), a missing “×12,” or you’re double-applying scaling (thousand/million).

2) Flip the switches and verify behavior

A lender-clean BESS Tolling Agreement block should behave predictably when you toggle inputs:

Turn CTA off → revenue should drop to zero across all years.

Turn availability adjustment off → applicable capacity should jump back to 100% (no haircut).

Turn curtailment adjustment on → you should see a small reduction consistent with the curtailment assumption (if modeled).

If the model doesn’t react cleanly, it’s usually an anchoring problem or a flag not being applied consistently.

The most common pitfalls (and why they matter)

Pitfall 1: Treating CTA like energy revenue.

CTA is paid on kW-ac, not MWh. If you accidentally anchor the revenue to delivered energy, you’ll mix dispatch assumptions into a structure that is meant to be stable and contracted.

Pitfall 2: Applying curtailment haircuts when curtailment is compensated.

If the contract pays through curtailment, applying a curtailment reduction understates revenue and can distort financing conclusions—especially in tight DSCR cases.

Pitfall 3: Ignoring the nameplate/deliverability boundary.

Even though tolling is contracted, the product is still a duration-defined deliverability obligation. If you don’t include a safeguard (or you never test it), you can unknowingly overstate “contracted” cashflows in scenarios where deliverability would be at risk.

Pitfall 4: Hiding escalation inside formulas.

Hardcoding “2% growth” deep in the revenue calculation makes sensitivities messy and error-prone. Keeping escalation as a time series is cleaner and more auditable.

Next, we’ll zoom out briefly and explain why this structure is the baseline lenders like—and how the logic evolves once you move from pure tolling into hybrid structures like resource adequacy or merchant overlays.

Why lenders like tolling (and what changes in other stacks)

From a project finance perspective, a BESS Tolling Agreement is the clean baseline because it turns a battery into something that looks and underwrites more like infrastructure: contracted capacity rent with predictable escalation. That stability matters because it reduces the number of moving parts a lender has to finance. Instead of debating market spreads, dispatch strategy, and volatility, the credit story concentrates on a smaller set of questions: Is the contract valid for the full term? Will the asset meet the performance rules? And are the assumptions conservative enough to protect debt service?

What debt and equity “see” under tolling

Under a pure BESS Tolling Agreement, debt and equity start from the same top-line revenue profile—contracted, indexed, and not directly exposed to merchant pricing. The differentiation happens through overlays:

lenders may assume more conservative availability unless there is a strong long-term service agreement with meaningful guarantees,

lenders will stress performance and downside cases to protect DSCR, and

lenders will care deeply that the model’s “applicable capacity” logic is rigorous (so there is no hidden overstatement).

In other words, tolling can be the most bankable structure in the model—but only if the mechanics are modeled cleanly.

What changes when you move beyond tolling

Once you step into resource adequacy hybrids or merchant-exposed cases, the revenue stack stops being a single contracted bar. The model needs to capture:

more complex payment bases (capacity + performance + merchant components),

greater sensitivity to operating strategy (cycling intensity),

and stronger interaction between revenue structure, degradation, augmentation timing, and ultimately financing capacity.

That’s why tolling is the right starting point: it establishes a transparent baseline and a disciplined modeling framework. In the next lesson and related structures, you’ll reuse the same best-practice architecture—flags, indexation series, applicable capacity logic—but you’ll add layers that reflect the real risk-return tradeoff across different monetization strategies.

Wrap-up and next steps (Deal Lab + RVA Certification)

A BESS Tolling Agreement revenue model can be deceptively simple on paper, but lender-grade in practice when you build it with the right structure: a clean contract flag, real-to-nominal price escalation, applicable capacity in kW-ac, and the correct performance adjustments (availability vs curtailment) plus a deliverability safeguard that keeps the cashflows honest. Once that block is solid, everything downstream—DSCR, debt sizing, equity returns, and sensitivities—rests on a foundation you can actually defend.

If you want to implement this hands-on exactly as shown, the BESS Deal Lab (Project Pulse) walks you step-by-step through the full model build, with the Project Pulse case materials and the Excel workflow so you can replicate every output in your own file.

And if you want the broader, structured path to mastering renewable energy project finance modeling (beyond one revenue stack or one case study), the RVA Certification Program gives you access to the full curriculum—so you can build repeatable skills across structures, technologies, and difficulty levels.

FAQs

What is a BESS Tolling Agreement, and how does it generate revenue?

A BESS Tolling Agreement is a contracted capacity arrangement where an offtaker effectively “rents” the battery’s AC capacity at the point of interconnection for a fixed payment—typically quoted in $/kW-ac-month—over a defined term. The offtaker controls dispatch, and the project earns revenue for making contracted capacity available rather than for selling energy on a merchant basis.

In a financial model, that means tolling revenue is primarily driven by four elements:

Applicable contracted capacity (kW-ac) at the POI,

the contract price in $/kW-ac-month,

escalation/indexation over time (e.g., a 2% annual curve), and

performance rules that determine what gets paid (most importantly availability, and whether curtailment is compensated).

Because it is contracted and typically indexed, a BESS Tolling Agreement is often considered the cleanest baseline revenue structure for project finance—but only if the “applicable capacity” logic correctly reflects contract rules and performance adjustments.

Why is tolling revenue modeled in kW-ac (not MWh), and what’s the most common unit mistake?

Tolling is a capacity product, so payments are based on reserved AC capacity at the point of interconnection, not on energy delivered. That’s why a BESS Tolling Agreement is priced in $/kW-ac-month: the offtaker is paying to have capacity available, regardless of how aggressively the battery is dispatched.

The most common mistake is a unit mismatch—for example:

using MW instead of kW (off by 1,000), and/or

forgetting the “×12” annualization implied by “per month” pricing.

A quick back-of-the-envelope check prevents both errors:

200 MW = 200,000 kW.

So annual revenue should roughly be 200,000 × price × 12, before escalation and any performance haircuts. If your first-year output is wildly off, it’s almost always a kW/MW issue, a missing ×12, or incorrect scaling to $000s.

How should availability and curtailment be treated under a BESS Tolling Agreement?

The correct treatment depends on what the contract compensates—so the model should reflect the payment rules, not a generic “haircut everything” approach.

A common structure (and the one highlighted in this Deal Lab case) is:

Unavailability is not compensated: if the BESS is down due to technical issues, the offtaker does not pay for the unavailable portion. In the model, this means you typically apply an availability adjustment to applicable capacity (or to the capacity payment).

Curtailment is compensated: if the system operator curtails the project for grid reasons, the capacity payment continues. In that case, you generally do not apply a curtailment haircut to tolling revenue.

Best practice is to implement both as explicit on/off switches in the revenue block. That keeps the model transparent and lets you reflect alternative contract language or lender overlays without rebuilding formulas.

What is “applicable capacity,” and why can’t you just assume 100% of nameplate gets paid forever?

“Applicable capacity” is the portion of contracted POI capacity that is actually eligible for payment in a given period after you apply the contract’s rules and performance adjustments. In a clean model, it typically starts with:

Contracted POI kW-ac × contracted proportion

…and then applies the relevant adjustments (availability, and possibly curtailment depending on compensation).

The reason you can’t blindly assume “100% of nameplate gets paid forever” is that the product being sold is ultimately a deliverability-defined AC product. Over long horizons, degradation and augmentation policy determine whether the BESS can continue meeting its contractual deliverability requirements. A lender-clean model therefore includes a safeguard that prevents overstatement if deliverability would ever fall below the contracted obligation—especially in stress tests (e.g., if augmentation is turned off or delayed).

In other words: contracts create stability, but physics still applies. The model’s job is to make sure the cashflows respect both.

How do you model escalation for a BESS Tolling Agreement without hardcoding it into the revenue formula?

The cleanest approach is to separate commercial inputs from time-series mechanics:

Enter the tolling price as a real contract price (e.g., $9.5 per kW-ac-month) in your time-independent inputs.

Define the escalation as a time series in the time-dependent sheet (e.g., a 2% per annum index curve).

Convert real → nominal by multiplying the real price by the chosen index series (selected via a dropdown/lookup), and then use that nominal price in the revenue calculation.

This is better than hardcoding “×1.02^t” inside your revenue formula because it makes the model:

more transparent (you can see the escalation curve directly),

easier to sensitivity test (swap curves without rewriting formulas),

and more lender-friendly (clean separation of assumptions and calculations).

How do you quickly sanity-check a BESS Tolling Agreement revenue line?

Use a two-step check: one back-of-the-envelope magnitude test and one behavior test.

1) Magnitude test (should be in the right ballpark):

Compute an approximate first-year revenue:

POI kW-ac × $/kW-month × 12

For a 200 MW system, that’s 200,000 kW. If your modeled first-year revenue is nowhere near that range (before escalation and haircuts), you likely have a kW vs MW issue, missed the ×12, or applied the wrong scaling to $000s.

2) Behavior test (the model should react cleanly):

Toggle a few key switches and confirm the output responds exactly as expected:

turn the CTA revenue stream off → revenue goes to zero everywhere

turn availability adjustment off → applicable capacity increases (no haircut)

if curtailment is compensated, keep curtailment adjustment off and confirm revenue doesn’t drop when curtailment changes

If these don’t work cleanly, the issue is usually missing flag multiplication or incorrect cell anchoring.

Why do lenders often underwrite a more conservative availability assumption than equity under a tolling contract?

Even under a fully contracted tolling structure, lenders are underwriting debt service reliability, not upside. If the contract does not compensate unavailability, then availability becomes a direct revenue risk: every percentage point of downtime can translate into a proportional reduction in capacity payments (depending on the contract’s measurement and settlement mechanics).

Equity may be comfortable assuming availability that aligns with vendor expectations or long-run averages—especially if they believe operations will outperform. Lenders, however, typically want to ensure the project can still service debt under conservative conditions, which is why they may:

apply a tighter downside availability case, and/or

look for a strong long-term service agreement (LTSA) with meaningful availability guarantees and remedies that effectively support the contracted payment profile.

In practical modeling terms, this is exactly why your tolling revenue block should be built with an explicit availability adjustment switch and clear inputs—so “lender case vs equity case” becomes a transparent assumption change, not a hidden spreadsheet rewrite.

Where can I follow along and build this BESS Tolling Agreement model step-by-step?

You can follow the exact workflow in the BESS Deal Lab (Project Pulse). The Deal Lab walks you through building the full Project Pulse model in Excel—starting from the information memorandum and inputs, then implementing the BESS Tolling Agreement revenue logic (flags, escalation, applicable capacity adjustments), and finally tying it into clean project finance outputs like cashflow waterfalls, dashboard KPIs, and financing metrics. It’s designed so you can replicate every step hands-on rather than just reading about the concept.

How does the RVA Certification Program fit in if I want to master project finance modeling beyond this tolling case?

The RVA Certification Program is the complete learning path that takes you from fundamentals to advanced, investor-grade renewable energy modeling—so you can apply the same disciplined approach not only to tolling, but also to hybrid contracted structures, merchant overlays, downside cases, and financing decisions across technologies. The Deal Lab is a deep case study experience; the RVA Certification is the broader framework that builds repeatable skills and gives you access to the full curriculum so you can grow from “I can follow this one model” to “I can build, analyze, and defend models across deals.”